Five Common Mistakes in Natatorium Design

Time and time again we visit indoor pools with fundamental design flaws that just make us scratch our heads and wonder ..."why?"

We have come to recognize that nobody knows what they don't know. This is especially true in a niche like indoor swimming pools, because there are so few of them. That's part of the dilemma facing mechanical engineers tasked with designing natatorium facilities. They don't have much to work with unless they have personal experience. This article outlines the five (5) most common mistakes we see in indoor pools.

Covered in this article:

- Ceiling exhausts

- Low returns

- Not using a pool dehumidifier

- Conflicting airflow

- Lack of communication

- Conclusion

While the biggest mistake could be building the wrong pool for how it will be used, this article focuses on just the mechanical design aspects. In other words, we're talking about air systems, not the entire natatorium.

Natatoriums are unlike any other type of room. Just ask an engineer who has had to design one. There are many factors in natatoriums that do not exist in rooms without swimming pools. Natatorium designs must go far beyond moisture removal and energy efficiencies.

5. Ceiling Exhausts

Ceiling exhausts may make sense in some applications, but not in a natatorium. Yes, heat and humidity rise, so you can alleviate the moisture demands by exhausting from up high. But air quality is a far more critical and problematic issue.

Chloramines and other disinfection byproducts (DBP’s) off-gassing from the swimming pool itself are heavier than oxygen, and stay low in the room. So what good does a ceiling exhaust do for heavy, contaminated air?

It is vital to keep the user experience in mind when designing an indoor pool. Mechanical engineers may not think about things like chloramines unless they were competitive swimmers. We see this all the time. It’s not that engineers deliberately neglect IAQ—it’s just that most people misunderstand the source of bad air quality. Not many engineers know that these off-gassing DBP’s stay low in the room. Or they believe its just a problem that can (and should) be resolved by fixing the pool chemistry.

Moreover, unless you have personal experience getting sick and miserable in a swimming pool, it’s difficult to relate to how severe the IAQ problem can be for natatoriums...even when they have excellent water chemistry and state-of-the-art pool equipment and secondary disinfection. Chloramines will still off-gas, and they become an air problem at that point. Ceiling exhausts can do nothing about them.

So in terms of air quality, they are useless, and can actually conflict with effective airflow needed to clear the space of chloramine pollution.

Remedy

Rather than exhausting up high, dedicated exhausts should be low, and specially designed for source capture. Such technology does exist and is highly effective. Simply putting low exhausts in the room is usually not enough, as we have seen around the country in dozens of cases. Our facility evaluation provides on-site instruction and a detailed report on how to do this correctly. Effective exhaust works best when it exhausts the optimum air volume, at the right velocity, with the correct static pressure, in the best location available.

Standard exhausts just pull air out of the room. But it's usually the wrong air.

4. Low Returns

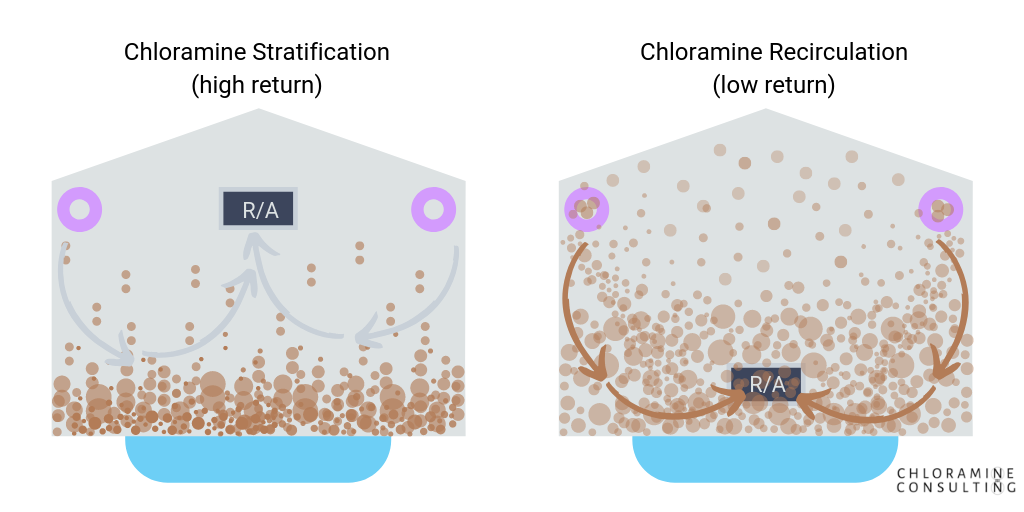

From an ASHRAE design standpoint, low returns sound like a decent idea. In reality, however, they recirculate chloramines through the dehumidifier.

The logic behind low returns is one of semantics: “returns” and “exhausts” are sometimes used interchangeably because modern pool dehumidifiers tend to have their exhaust blower located in the return path. The problem with this should be obvious: the exhaust blower has no way of distinguishing the good air from the bad.

Low returns create two significant problems for an indoor swimming pool.

Corroded evaporator coils in a pool dehumidifier

First, chloramines and other DBP’s tend to have a very low pH, which means this contaminated air corrodes and rusts virtually everything it passes by. When this moisture condenses on metal surfaces, in particular, rust is rampant. A good analogy is chain-smoking cigarettes. That fancy pool dehumidifier is basically chain-smoking chloramines, and the inside may be corroded severely because of it. This is a very costly mistake that can open designers up to risk and liability.

Second, recirculating chloramines blows them back into the natatorium! From the supply ducts, chloramines fall right back down to the breathing zone. Sure, you’re moving them around, but are you really getting rid of them? No. The only chloramines leaving the space are the ones that happen to get pulled out of the exhaust fan...wherever it may be.

If the facility uses a 100% outside air system, however, low returns are not necessarily a bad idea...provided there are also returns up high to grab the warm, humid air too.

Remedy

Low returns can be okay, but not without source-capture exhaust. If your entire exhaust is within the return path, problems are inevitable, for reasons just explained. We never design return(s) to handle all the air in the natatorium, period. We always want a dedicated low source-capture exhaust.

3. Not using a pool dehumidifier

Air conditioners are NOT the same as pool dehumidifiers. They are not an adequate substitute for them either. We have another article explaining the major differences between air conditioning and dehumidification here.

Air conditioners are great at what they do, but they are not designed for anywhere near the demands of an indoor pool or spa. In our experience, putting an air conditioner on a natatorium is a big mistake. An air conditioner's purpose is to maintain a temperature, whereas a pool dehumidifier's purpose is to maintain a relative humidity, dew point AND temperature. Yes, pool dehumidifiers are more expensive, and that's because they have a lot more functionality inside.

Never fall for the trap of value engineering a PDU off the project in favor of air conditioners. It never works well. Indoor pools have much more moisture to remove than an air conditioner can handle.

Additionally, a pool dehumidifier should be robust enough to overcome large temperature differentials (𝚫T) between the outside air and the desired inside temperature. A freezing cold day outside takes a lot of heat to bring up to 84ºF. A pool dehumidifier usually has a pre-heat coil that yields significant energy savings.

Remedy

Get a properly sized pool dehumidifier with a good duct design. If not a pool dehumidifier, you can also opt for a pool unit that is a dedicated outside air unit (DOAS), but the energy costs are substantial.

2. Conflicting airflow

Let’s talk about where the supply air flows in the natatorium. First of all, think about the objectives of conditioned supply air. The entire ASHRAE design handbook has only four (4) pages about natatorium design. These four pages in ASHRAE 62.1 mention excellent information, but much is left open to interpretation. We have personally visited hundreds of natatoriums that met the ASHRAE design handbook guidelines, yet their IAQ was abysmal. Why?

Let’s talk about where the supply air flows in the natatorium. First of all, think about the objectives of conditioned supply air. The entire ASHRAE design handbook has only four (4) pages about natatorium design. These four pages in ASHRAE 62.1 mention excellent information, but much is left open to interpretation. We have personally visited hundreds of natatoriums that met the ASHRAE design handbook guidelines, yet their IAQ was abysmal. Why?

Natatorium IAQ is a very delicate thing. 90% of the design can be spot on, and the other 10% could negate it all. Based on our experience, very seldom are entire natatorium HVAC designs flawed. It’s almost always one or two seemingly-small things that cause the problems. Everything needs to work together in harmony, and air needs to be moving in the right direction, at the right speed.

Where is your supply air going, and how fast is the air moving? Is it getting to the breathing zone at all? And if so, how, and where? Where is your supply air moving relative to your return(s) and exhaust(s)? From a holistic view of air movement in the entire natatorium, what is happening? Too often, we see designs that focus on the trees and never see the forest. The result is conflicting airflow and designs that don’t make sense. For example: blowing air directly toward a return vent, or exhausting the best air in the room while ignoring the worst.

Remedy

Start any design project by thinking of the swimmers and lifeguards. What are you trying to accomplish for them? How will they be using the facility? How can you—the design professional they depend on—provide clean and healthy air to them? How will you address the airborne chloramines and other harmful DBP’s that will inevitably be off-gassing from the pool? Start with the end-users in mind, and work backward to accomplish those goals.

1. Lack of Communication

We saved the most severe mistake for last. Communication and coordination is something that needs to happen a lot more. Aquatics and air people often never meet each other. When problems arise, everyone is quick to point their fingers at others. However, the reality is this: without coordination between both sides, bad air quality is almost guaranteed.

Most importantly, it's the swimmers and lifeguards who suffer the most. And they're not even involved in the design/build process. They depend on the professionals to do things right.

When things fail, natatoriums are forced to spend big money on replacing expensive components within their dehumidifier(s) to be able to keep the facility operating. The two most common replacements we see are uncoated evaporator coils and compressors. Not only do these components get corroded by chloramines beyond belief, but they also fail way before their life expectancy. These problems are rarely the fault of the dehumidifier manufacturer.

With some questions and investigation, we discover that pool operation practices are usually part of the issue. Actions are taken (or not taken) by people who did not know they were doing anything wrong. Some examples:

- opening doors to get fresh air to coughing swimmers;

- turning the air temperature down because people are uncomfortable;

- turning the water temperature up to satisfy complaining patrons;

- shocking the pool with excessive chlorine;

- hosting swim meets with massive bather loads, etc.

We have seen pool dehumidifiers designed for an 82ºF pool, and the pool operators run the pool at 88ºF. However, nobody told the design engineer or the dehumidifier manufacturer. Conversely, nobody told the pool operator their HVAC system could not handle that. Had the mechanical engineer known the pool would be operated at 88ºF, the dehumidifier would have been built for it.

The victims of this lack of coordination are the facility owner, maintenance staff, and most importantly, the swimmers. Don’t forget about the design engineers who are responsible for their work, and the equipment manufacturers involved. Nobody wins.

Remedy

Even if coordination and communication happen, it is sometimes difficult to translate between water and air/HVAC jargon. The remedy for this is to simplify the information so all parties can understand. Be as detailed as needed in your world; but for coordination, simplify.

Conclusion

Natatoriums are a scary thing for an engineer to design because of the unknowns. So many things can go wrong. It’s not like an office building or school. Natatoriums have humidity and moisture extremes, directional airflow requirements, enormous energy demands, and of course, a swimming pool that off-gasses harmful, contaminated air. Furthermore, a natatorium can be designed within ASHRAE handbook guidelines and still have horrible IAQ.

Chloramine Consulting exists to bridge the gap between water and air. We guide engineers through potential IAQ problems and show how to prevent them. We also facilitate communication between air and aquatics, ensuring the facility’s HVAC design matches the pool, and vice versa. Finally, we simplify information so that all parties involved—especially pool operators—know what is going on. These mistakes (and many more) can be avoided.

By

By